Smart Stents

The Straits Times, Mind Your Body, 24 January 2013, By JOAN CHEW

Biodegradable stents are hailed as the next big thing in the treatment of blocked heart arteries

Just as a cast holds a broken bone in place while it heals, but is removed eventually, a new type of stent props an artery open and then dissolves in the body after two years.

Such a concept appeals to both doctors and patients: After completing its job, the stent leaves nothing behind in the heart, unlike conventional stents, which are permanent implants.

Once the stent has dissolved, the treated vessel can resume its natural pulsing movements, responding to increased demand for blood flow during activities such as exercise, without being constrained by any stent.

The first biodegradable stent was approved by the Health Sciences Authority here on Dec 20 last year, paving the way for doctors to use it routinely on patients with coronary artery disease.

Branded Absorb by manufacturer Abbott, it is made of polylactide, a naturally soluble material that is commonly used in medical procedures such as those involving dissolving sutures.

As with all other stents for the heart, the Absorb stent is a class D, or high-risk, medical device.

Checks with both national heart centres and six other hospitals here, public and private, showed they had, in total, implanted close to 150 Absorb stents in more than 100 patients here.

Doctors at the National University Heart Centre, Singapore (NUHCS) started using the new stent from February 2011 as part of a global clinical trial that is still on, said its director, Associate Professor Tan Huay Cheem.

More than 600 patients have taken part in the trial, which aims to have 1,000 patients from up to 100 centres in Europe, the Asia-Pacific, Canada and Latin America.

Some hospitals, such as Alexandra Hospital and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (KTPH), are not using the new stent. Dr Lee Yian Ping, a consultant at the department of cardiology at KTPH, said it is too early to tell if Absorb is safer or more effective than conventional stents.

But results from some small-scale studies, coupled with the theoretical benefits of a disappearing stent, are compelling reasons for many doctors to hail it as a significant development.

Prof Tan said the race to create a perfect biodegradable stent started as soon as the idea was first conceived 30 years ago.

It took Abbott nearly a decade to develop and commercialise its stent, which is now available in Europe, the Middle East, parts of Latin America and parts of Asia, such as India, Hong Kong, the Philippines and Vietnam.

Researchers from Nanyang Technological University (NTU) are also working on dissolving stents made of other materials.

Professor Freddy Boey, provost of NTU and Professor Subbu Venkatraman, chair of the school of material science and engineering, founded biotechnology firm Amaranth Medical to take the NTU device to clinical trials and will start them in the South merican country of Colombia this month.

Prof Venkatraman estimated it will be two to three years before their stent is approved for use.

Opening blocked arteries

Coronary artery disease is the slow, progressive narrowing of the three main arteries and their branches that supply blood to the heart.

This narrowing occurs when fatty substances, such as cholesterol, accumulate on the inner lining of an artery in a process called atherosclerosis.

When the disease advances to a stage where it significantly diminishes the blood flow to heart tissues, patients experience chest pain known as angina.

At times, angina may cause nausea, shortness of breath and sweating.

When chest pain occurs at rest, it is classified as unstable angina.

Dr Teo Swee Guan, a specialist in cardiology and consultant at Raffles Heart Centre at Raffles Hospital, said medicine which reduces the demand for blood flow to the heart is the first-line treatment to control the symptoms of angina.

But when this does not provide adequate relief or a person suffers a heart attack from a coronary artery becoming totally obstructed, surgical procedures can be used to improve blood flow, either by bypassing arteries or by stretching them.

A bypass involves harvesting a vessel from another part of the body and grafting it to healthy heart arteries. This creates a new channel for blood to flow through, avoiding a blocked artery.

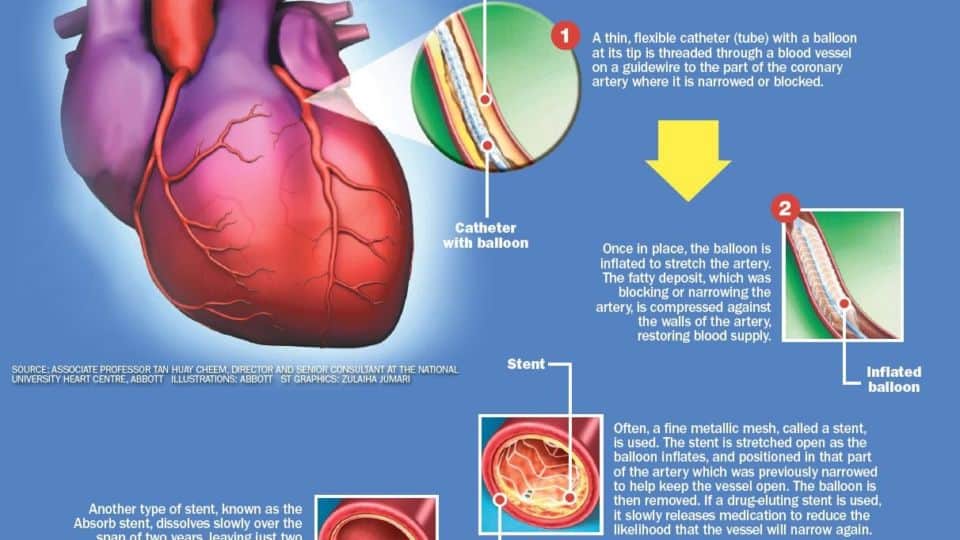

The procedure to stretch the artery is called angioplasty, in which a balloon is inserted in the artery through a guidewire and then inflated at the site of the blockage.

In more than 95 per cent of the cases, a stent is implanted after the balloon procedure to hold the artery open, said Prof Tan.

Patients who could not have stents implanted in them either have blockages in arteries that are too small or a blocked passage that is too long for a stent.

Doctors now use either bare metallic stents or drug-eluting stents (coated with drugs that are released over time) to provide additional protection against restenosis, or the re-narrowing of the artery.

The Absorb stent delivers everolimus, a drug that prevents abnormal growth of tissue due to scarring, to prevent restenosis.

Dr Goh Yew Seong, a consultant in cardiology at Changi General Hospital, said the type of stent used depends on the patient’s acute physical condition, existing medical problems and anatomy.

He estimated that 10 to 20 per cent of patients with drug-eluting stents can be offered the biodegradable stent, though this could increase with evolving technology.

Dr Dinesh Nair, a senior consultant at the Parkway Heart and Vascular Centre at Mount Elizabeth Novena Hospital, said doctors should tamper patients’ expectations of the new technology.

There is only about four years of patient data on the Absorb stent, whereas bare metallic stents have been tested for more than two decades and drug-eluting stents have been used for more than a decade.

Better long-term benefits?

However, doctors are eager to see how patients do on these new stents over the long term.

Dr Charles Chan, a cardiologist at Gleneagles Medical Centre and Gleneagles Hospital, said his main concern with existing stents is the risk of blood clots forming around the stent after a year. This is known as very late stent thrombosis.

A blood clot could block the flow of blood through the artery and cause a heart attack.

This risk of very late stent thrombosis, though rare at about 1 to 2 per cent a year, exists for all types of metallic stents, including drug-eluting ones.

Dr Chan said the use of biodegradable stents would make this complication a thing of the past.

Dr Paul Ong, a senior consultant at the department of cardiology at Tan Tock Seng Hospital, noted that current metallic stents are impossible to remove once implanted inside arteries.

If a patient with a metallic stent were to require a bypass in future, it would be almost impossible for the surgeon to connect a new vessel to the vessel with the stent, he explained.

But this would no longer be an issue once the stent is absorbed by the body, he said.

When 27 of the first 30 patients in the Absorb trial arrived at the four-year mark, none had stent thrombosis and the rate of major adverse cardiac events – defined as cardiac death, heart attack or the need for a repeat procedure – was 3.4 per cent.

Nine-month results from 101 patients enrolled in a second trial showed that this rate was at 5 per cent, with no reports of blood clots.

Such results show the new stent is as safe as regular stents, doctors said.

For instance, a randomised trial of 1,800 patients comparing two types of drug-eluting stents – paclitaxel-eluting and everolimus-eluting stents – showed that the rate of major adverse cardiac events at 12 months was 9.1 per cent and 6.2 per cent respectively.

Dr Eric Hong, a senior consultant interventional and nuclear cardiologist in private practice at Mount Elizabeth Medical Centre, said that patients implanted with drug-eluting stents need to take two anti-clotting or anti-platelet drugs – aspirin and clopidogrel– for at least a year to prevent clots from forming around the stent. They then usually continue with a cheaper drug, such as aspirin, indefinitely.

But the new soluble stent may make it possible for some patients who are clinically stable and have increased risk of bleeding in the stomach from aspirin to stop taking even that eventually.

Dr Hong said: “The thought is, if there is no implant left behind that could cause stent thrombosis, it is plausible to stop the anti-platelet therapy.”

However, the Absorb stent does pose some challenges.

Associate Professor Philip Wong, a senior consultant at the department of cardiology and director of the research and development unit at National Heart Centre Singapore, said it is harder to see the new stent on the X-ray guide during surgery than regular metal stents, because the material does not show up on X-ray.

Instead of the full stent, only four tiny platinum markers can be seen.

The new stent is also technically more difficult to insert because it has thicker struts than regular stents, he added.

But he believes biodegradable stents may become the standard choice for opening blocked arteries in time to come.

Prof Wong said: “Studies have shown that the healing of the artery is very good half a year after the procedure, with the entire stent covered by vessel tissue.

“Furthermore, as the stent dissolves away, it allows natural healing and recovery of the vessel, unlike a permanent metal stent which acts like a ‘cage’ restricting vessel motion over the longer term.”